Deep Learning Performance Improvement 4 - Back-propagation

Back-propagation

Importance of Back-propagation

Due to improvement of open source tools like Tensorflow or Keras, it seems easier to code up classification of cat or dog based on CNN without understanding. Unfortunately, these tools let us be tempted to avoid understanding of the algorithms. In particular, not understanding back-propagation would most probably lead you to badly design your networks. In a Medium article, Andrej Karpathy, now director of AI at Tesla, listed few reasons why you should understand back-propagation. Problems such as vanishing and exploding gradients, or dying relus are some of them. Back-propagation is not a very complicated algorithm, and with some knowledge about calculus especially the chain rules, it can be understood pretty quick.

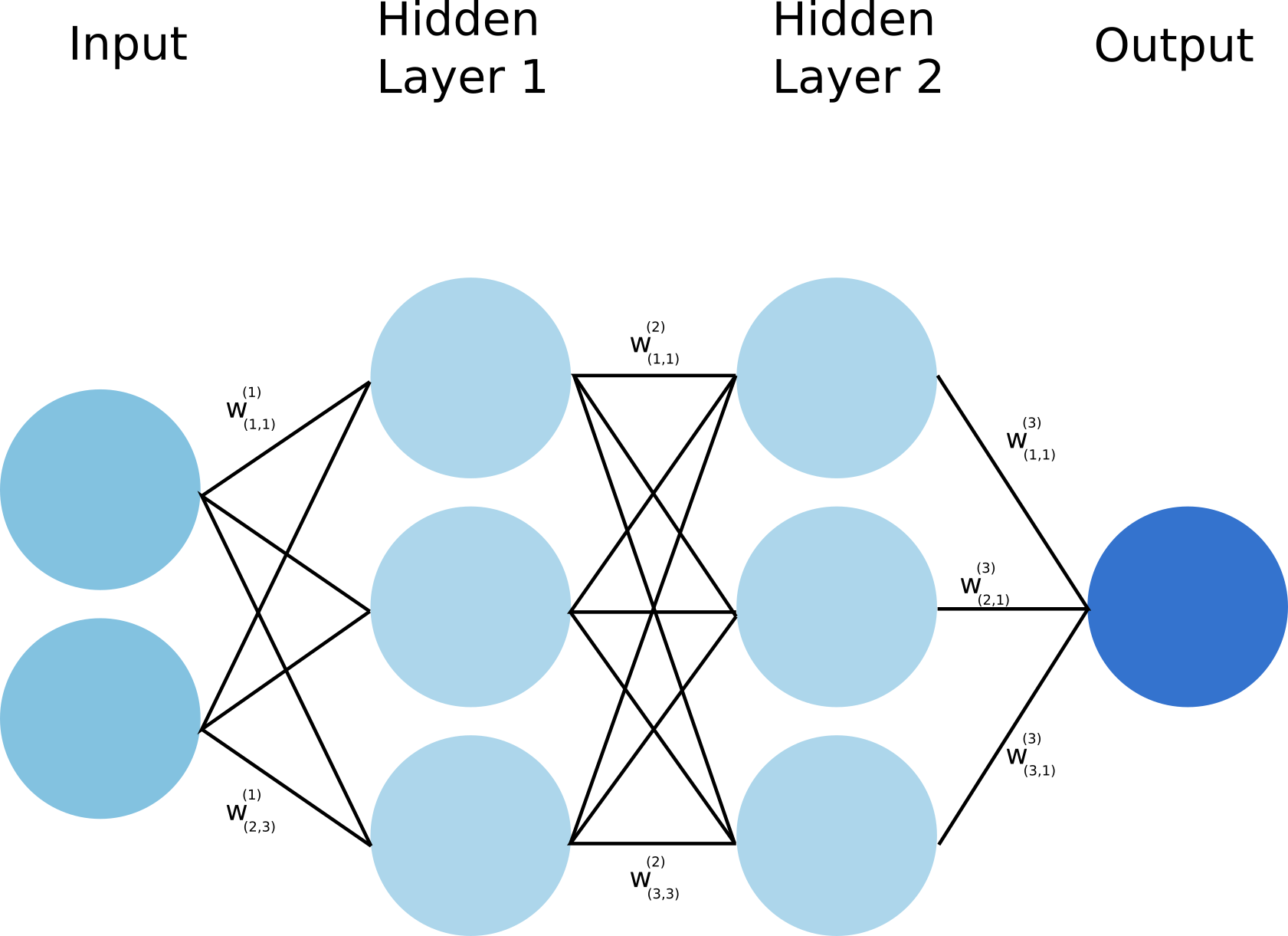

Neural networks, like any other supervised learning algorithms, learn to map an input to an output based on some provided examples of (input, output) pairs, called the training set. In particular, neural networks performs this mapping by processing the input through a set of transformations. A neural network is composed of several layers, and each of these layers are made of units (also called neurons) as illustrated below:

The input in the Figure 1 is transformed into the hidden layer 1 and 2 sequantially up to the outputs as prediction. Each transformation is controlled by a set of weights and biases. During training, to indeed learn something, the network needs to adjust these weights to minimize the error (also called the loss function) between the expected outputs and the ones it maps from the given inputs. Using gradient descent as an optimization algorithm, the weights are updated at each iteration as:

\(w^{(n+1)} = w^{(n)} - \epsilon \frac{\partial L}{\partial w}\), where L is the loss function and \(\epsilon\) is the learning rate.

As we can see above, the gradient of the loss w.r.t. the weight is substracted from the weight at each iteration. This weight updating process that guides the direction of a model to global minimum gradually is called gradient descent. The gradient \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial w}\) can be interpreted as a measure of the contribution of the weight to the loss. Therefore the larger is this gradient (in absolute value), the more the weight is updated during an iteration of gradient descent.

The minimization of the loss function task ends up being related to the evaluation of the gradients described above. We will review 3 proposals to perform this evaluation:

- Analytical calculation of the gradients.

- Approximation of the gradients as being: \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial w} = \frac{L(w + \delta w) - L(w)}{\delta w}\), where \(\delta w \rightarrow 0\).

- Backpropagation or reverse mode autodiff.

Before explore the analysis of back-propagation, let’s define our problem and simplify it for the sake of the discussion.

1 - Problem definition

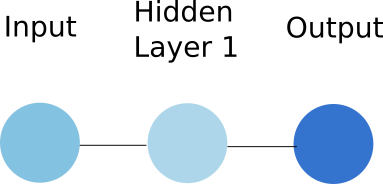

To simplify our discussion, we will consider that each layer of the network is made of a single unit, and that we have a single hidden layer. The network looks now like:

Figure 2 shows how the input is transformed to produce the hidden layer representation. In neural network, a layer is obtained by performing two operations on the previous layer:

- First the previous layer is tranformed via a linear operation: the value of the previous layer is multiplied by a weight, and a bias is added to it. It gives: \(z = xw + b\), where x is the value of the previous layer unit, w and b are respectively the weight and the bias discussed above.

- Second, the previous linear operation is used as an input to the activation function of the unit. This activation is generally chosen to introduce non linearity in order to solve complex tasks. Here we will simply consider that this activation function is a sigmoid function: \(\sigma(x) = \frac{1}{1+\exp(-x)}\). As a consequence the value y of a layer can be written as: \(y = \sigma (z) = \sigma (xw + b)\), with x, w and b defined as above.

From the input layer \(x\), through hidden layer \(h\), to output layer \(y\), we can write:

\(h = \sigma (xw_1 + b_1)\), where \(w_1\) and \(b_1\) are respectively the weight and the bias used to compute the hidden unit from the input.

\(y = \sigma (hw_2 + b_2)\), where \(w_2\) and \(b_2\) are respectively the weight and the bias used to compute the output from the hidden unit.

From now on, we are able to calculate the output y based on the input x, through a set of transformations. This is the so called forward propagation since this calculation goes forward inside the network.

We now need to compare this predicted ouptut to the true one \(y_T\). As explained earlier, we use a loss function to quantify the error that the network does while prediciting. Here we will consider as a loss function the squared error defined as :

\[L = \frac{1}{2} (y-y_T)^2\]The weight (with biases) updating prothe process if important for the gradient of this loss function L w.r.t. these weights (and biases). Naive approach of evaluating these gradients suffers against computational difficulty. Thus, the idea of Euler’s method was taken with partial derivation for each layer.

np.random.seed(0)

def generate_dataset(N_points):

# 1 class

radiuses = np.random.uniform(0, 0.5, size=N_points//2)

angles = np.random.uniform(0, 2*math.pi, size=N_points//2)

x_1 = np.multiply(radiuses, np.cos(angles)).reshape(N_points//2, 1)

x_2 = np.multiply(radiuses, np.sin(angles)).reshape(N_points//2, 1)

X_class_1 = np.concatenate((x_1, x_2), axis=1)

Y_class_1 = np.full((N_points//2,), 1)

# 0 class

radiuses = np.random.uniform(0.6, 1, size=N_points//2)

angles = np.random.uniform(0, 2*math.pi, size=N_points//2)

x_1 = np.multiply(radiuses, np.cos(angles)).reshape(N_points//2, 1)

x_2 = np.multiply(radiuses, np.sin(angles)).reshape(N_points//2, 1)

X_class_0 = np.concatenate((x_1, x_2), axis=1)

Y_class_0 = np.full((N_points//2,), 0)

X = np.concatenate((X_class_1, X_class_0), axis=0)

Y = np.concatenate((Y_class_1, Y_class_0), axis=0)

return X, Y

N_points = 1000

X, Y = generate_dataset(N_points)

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

plt.scatter(X[:N_points//2, 0], X[:N_points//2, 1], s=10, color='red', label='class 1', alpha=0.5)

plt.scatter(X[N_points//2:, 0], X[N_points//2:, 1], s=10, color='blue', label='class 0', alpha=0.5)

plt.legend(loc=9, bbox_to_anchor=(0.5, -0.1), ncol=2)

plt.show()

1.1 - Example Dataset

Let’s consider a binary classification problem where the task is about predict the class of a given input. As a dataset, we chose a pretty standard not linearly separable dataset made of two classes “0” and “1”.

2 - Approaches for Differentiation

2.1 - Analytical differentiation (Computational Difficulty)

Now we are here for analytical derivation why it suffers against computational difficulty.

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_2} & = \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial \left((y-y_T)^2\right)}{\partial w_2} \\ & = \frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{\partial \left(y^2\right)}{\partial w_2} - 2y_T \frac{\partial y}{\partial w_2}\right)\\ \end{split} \end{equation}\]Knowing that \(y = \sigma (hw_2 +b_2)\), we get :

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_2} & = \frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{\partial \left(\frac{1}{\left( 1 + \exp(-hw_2 -b_2\right))^2}\right)}{\partial w_2} - 2y_T \frac{\partial \frac{1}{1 + \exp(-hw_2 - b_2)}}{\partial w_2}\right) \\ & = \frac{h \exp(-hw_2 - b_2)}{\left(1+\exp(-hw_2 - b_2)\right)^3} - \frac{y_T h \exp(-hw_2 - b_2)}{\left(1+\exp(-hw_2 - b_2)\right)^2} \\ & = h\frac{ \exp(-hw_2 - b_2)}{\left(1+\exp(-hw_2 - b_2)\right)^2} \left(\frac{1}{1+\exp(-hw_2 - b_2)} - y_T\right) \end{split} \end{equation}\]Here we derived the gradient w.r.t. \(w_2\), and the calculation for the one w.r.t. \(w_1\) would be even more tedious. That means, such an analytical approach would be exponentially complicated to implement for a “deep” neural network. In addition, computing wise this approach would be quite inefficient since we could not leverage the fact that the gradients share some common definition. A way more easy way to get these gradients would be to use a numerical approximation (Euler’s method).

2.2 - Numerical differentiation (Euler’s method)

Trading accuracy for simplicity, we can obtain the gradient using the following:

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w} \simeq \frac{L(w + \delta w) - L(w)}{\delta w}, \space with \space\delta w \rightarrow 0 \end{split} \end{equation}\]Numerical approach ease computational wise, but providing approximate soltuion. In addition before computing all the gradients, we would have to compute the loss function to update (doing one forward pass by weights and biases). That is, computational burden comes with size of parameters; for a neural network with 1 million weigth parameters, it would requires 1 million forward propagation, which is definitely not efficient to compute. To reduce such a burden by adjusting a better weight (with biases) and loss updating process, back-propagation can be introduced.

3 - Back-propagation

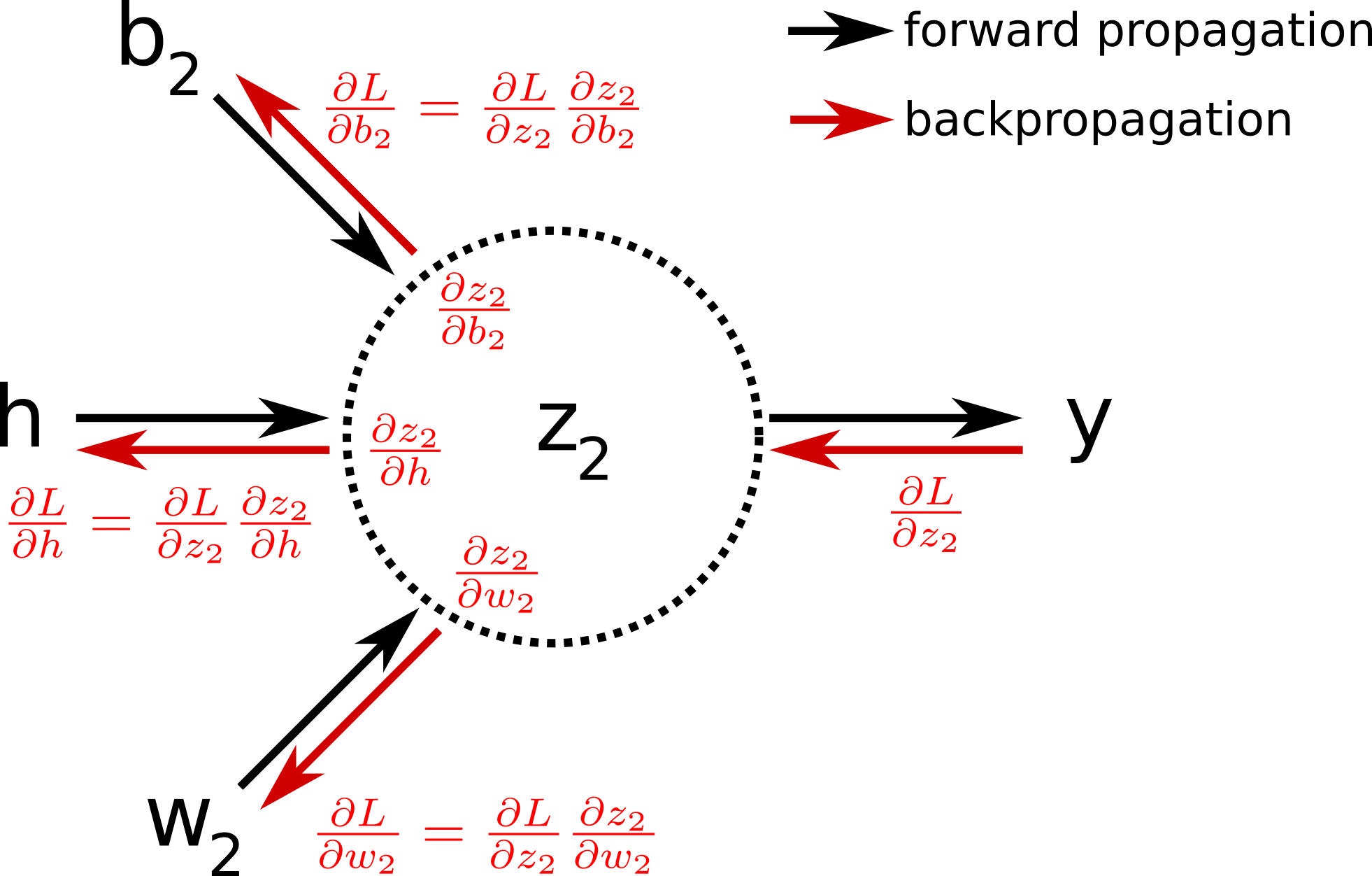

Before speaking in more details about what back-propagation is, let’s first introduce the computational diagram that leads to the evaluation of the loss function.

The nodes in this graph correspond to all the values that are computed in order to get the loss L. If a variable is computed by applying an operation to another variable, an edge is drawn between the two variable nodes. Looking at this graph, and making use of the chain rule of calculus, we can express the gradient of L with respect to the weights (or biases) as:

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_2} & = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial w_2}\\ & = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial w_2} \\ \end{split} \end{equation}\]Same goes for the weight \(w_1\):

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial L}{\partial w_1} & = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial w_1}\\ & = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial w_1} \\ & = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial h} \frac{\partial h}{\partial w_1} \\ & = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial h} \frac{\partial h}{\partial z_1} \frac{\partial z_1}{\partial w_1} \end{split} \end{equation}\]One very important thing to notice here is that the evaluation of the gradient \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial w_1}\) can reuse some of the calculations perfomed during the evaluation of the gradient \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial w_2}\). It is even clearer if we evaluate the gradient \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial b_1}\):

\[\begin{equation} \begin{split} \frac{\partial L}{\partial b_1} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial y} \frac{\partial y}{\partial z_2} \frac{\partial z_2}{\partial h} \frac{\partial h}{\partial z_1} \frac{\partial z_1}{\partial b_1} \end{split} \end{equation}\]We see that the first four term on the righ hand of the equation are the same than the one from \(\frac{\partial L}{\partial w_1}\).

As you can see in the equations above, we calculate the gradient starting from the end of the computational graph, and proceed backward to get the gradient of the loss with respect to the weights (or the biases). This backward evaluation gives its name to the algoritm: back-propagation. The back-propagation algorithm can be illustrated by the image below:

In pratice, one iteration of gradient descent would now require one forward pass, and only one pass in the reverse direction computing all the partial derivatives starting from the output node. It is therefore way more efficient than the previous approaches. In the original paper about backpropagation published in 1986 [4] , the authors (among which Geoffrey Hinton) used for the first time backpropagation to allow internal hidden units to learn features of the task domain.

To visualize better what backpropagation is in practice, let’s implement a neural network classification problem in bare numpy. Indeed as we will see below, there is no need of a complex deep learning library to play at first with a neural network.

4 - The neural network

As we can see from the dataset above, the data point are defined as \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\). Therefore the input layer of the network must have two units. We want to classify the data points as being either class “1” or class “0”, then the output layer of the network must contain a single unit. Between the input and the output layers, we add a hidden layer with 3 units. The full network looks like:

</center>

</center>

Choosing the right network architecture is more an art than a science, and there is no ground reason to choose the second layer to have 3 units. I encourage you to go and play with the tensorflow playground to realize that. We have already studied a similar architecture before but with a single unit per layer. The previous equations can be easily generalized for layers with more than one unit:

\(\mathbf{z_1} = \mathbf{W_1 x} + \mathbf{b_1}\), with \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{W_1} = \begin{bmatrix} w^{(1)}_{1,1} & w^{(1)}_{2,1} \\ w^{(1)}_{1,2} & w^{(1)}_{2,2} \\ w^{(1)}_{1,3} & w^{(1)}_{2,3} \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\), \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\) and \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{b_1} = \begin{bmatrix} b^{(1)}_{1}\\ b^{(1)}_{2}\\ b^{(1)}_{3}\\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\)

\[\mathbf{h} = \sigma(\mathbf{z_1})\]\(\mathbf{z_2} = \mathbf{W_2 h} + b_2\) with \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{W_2} = \begin{bmatrix} w^{(2)}_{1,1} & w^{(2)}_{2,1} & w^{(2)}_{3,1} \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\), and \(b_2 = b^{(2)}_1\).

\[\mathbf{y} = \sigma(\mathbf{z_2})\]The above equations allow to predict a single output given a single data point\(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\). Instead of looping over all the data points from the dataset and evaluation y from them, it is way more efficient to take advantage of the vectorization of the problem. Let’s consider the vector \(\mathbf{X}\) with the shape \((N_{points}, 2)\): \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{X} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1^{(1)} & x_2^{(1)} \\ x_1^{(2)} & x_2^{(2)} \\ . & . \\ . & . \\ . & . \\ x_1^{(N_{points})} & x_2^{(N_{points})} \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\)

where the upperscripts \(^{(i)}\) simply refer to the datapoints.

We can rewrite the equations vectorized:

\(\mathbf{Z_1} = \mathbf{X W_1^T} + \mathbf{1 b_1^T}\), with \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{1} = \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ . \\ . \\ . \\ 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\) a vector of shape \((N_{points}, 1)\) whose elements are all 1.

\[\mathbf{H} = \sigma(\mathbf{Z_1})\]\(\mathbf{Z_2} = \mathbf{H W_2^T} + \mathbf{1} b_2\), with \(\mathbf{1}\) is as defined above.

\[\mathbf{Y} = \sigma(\mathbf{Z_2})\]4.1 - Forward propagation

Let’s now implement the code for the forward propagation through the network.

weights = {

'W1': np.random.randn(3, 2),

'b1': np.zeros(3),

'W2': np.random.randn(3),

'b2': 0,

}

def sigmoid(x):

"""

Compute the sigmoid of x

Arguments:

x -- A scalar or numpy array of any size.

Return:

s -- sigmoid(x)

"""

s = 1/(1+np.exp(-x))

return s

def forward_propagation(X, weights):

# this implement the vectorized equations defined above.

Z1 = np.dot(X, weights['W1'].T) + weights['b1']

H = sigmoid(Z1)

Z2 = np.dot(H, weights['W2'].T) + weights['b2']

Y = sigmoid(Z2)

return Y, Z2, H, Z1

4.2 - Loss function

Previously, for simplicity we used the squared error as a loss function. It turns out that for a classification problem, this is not an appropriate choice as a loss function. Indeed the squared error is not able to distinguish bad prediction from extremely bad ones in a classification context. Here as a loss function, we will rather use the cross entropy function defined as:

\[L(y, y_T) = \frac{1}{N_{points}} \sum_{n=1}^{N_{points}}\left( -y_T^{(n)} \log(y^{(n)}) - (1-y_T^{(n)}) \log(1-y^{(n)})\right)\]where \(y^{(n)}\) is the output of the forward propagation of a single data point \(\begin{equation} \begin{split} \mathbf{x^{(n)}} = \begin{bmatrix} x^{(n)}_1 \\ x^{(n)}_2 \\ \end{bmatrix} \end{split} \end{equation}\), and \(y_T^{(n)}\) the correct class of the data point.

To understand why the cross entropy is a good choice as a loss function, I highly recommend this video from Aurelien Geron.

4.3 - Back-propagation

We have everything we need now to define the back_propagation function. First let’s write again down the gradient equations:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{W_2}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{Y}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Y}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}{\partial \mathbf{W_2}}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{b_2}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{Y}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Y}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}{\partial \mathbf{b_2}}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{W_1}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{Y}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Y}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}{\partial \mathbf{H}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{H}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}}{\partial \mathbf{W_1}}\] \[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{b_1}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{Y}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Y}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Z_2}}{\partial \mathbf{H}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{H}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}}\frac{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}}{\partial \mathbf{b_1}}\]We therefore need the following partial derivatives, which can be easily obtained:

\[\frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{Y}} = \frac{1}{N} \frac{\mathbf{Y}-\mathbf{Y_T}}{\mathbf{Y}(1-\mathbf{Y})}\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial\mathbf{Z_2}} = \frac{\partial L}{\partial\mathbf{Y}} .\left(\sigma(\mathbf{Z_2})(1-\sigma(\mathbf{Z_2}))\right)\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{W_2}} = \mathbf{H^T} \frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial\mathbf{Z_2}}\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{b_2}} = \left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial\mathbf{Z_2}} \right)^T\mathbf{1}\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{H}} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial\mathbf{Z_2}} \mathbf{W_2^T}\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}} = \frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{H}}.\left(\sigma(\mathbf{Z_1})(1-\sigma(\mathbf{Z_1}))\right)\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{W_1}} = \left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}}\right)^T\mathbf{X}\] \[\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{b_1}} = \left(\frac{\partial \mathbf{L}}{\partial \mathbf{Z_1}}\right)^T\mathbf{1}\]We can now define the code for the backpropagation:

def back_propagation(X, Y_T, weights):

N_points = X.shape[0]

# forward propagation

Y, Z2, H, Z1 = forward_propagation(X, weights)

L = (1/N_points) * np.sum(-Y_T * np.log(Y) - (1 - Y_T) * np.log(1 - Y))

# Backward propagation:

# back propagation: calculate dL/dW1, dL/db1, dL/dW2, dL/db2.

dLdY = 1/N_points * np.divide(Y - Y_T, np.multiply(Y, 1-Y))

dLdZ2 = np.multiply(dLdY, (sigmoid(Z2)*(1-sigmoid(Z2))))

dLdW2 = np.dot(H.T, dLdZ2)

dLdb2 = np.dot(dLdZ2.T, np.ones(N_points))

dLdH = np.dot(dLdZ2.reshape(N_points, 1), weights['W2'].reshape(1, 3))

dLdZ1 = np.multiply(dLdH, np.multiply(sigmoid(Z1), (1-sigmoid(Z1))))

dLdW1 = np.dot(dLdZ1.T, X)

dLdb1 = np.dot(dLdZ1.T, np.ones(N_points))

gradients = {

'W1': dLdW1,

'b1': dLdb1,

'W2': dLdW2,

'b2': dLdb2,

}

return gradients, L

4.4 - Training: gradient descent

We have all in place to start training our network using gradient descent. Remember, at every iteration the weights and the biases are updated as \(w^{(n+1)} = w^{(n)} - \epsilon \frac{\partial L}{\partial w}\).

epochs = 2000

epsilon = 1

initial_weights = copy.deepcopy(weights)

fw_bk_losses = []

for epoch in range(epochs):

gradients, L = back_propagation(X, Y, weights)

for weight_name in weights:

weights[weight_name] -= epsilon * gradients[weight_name]

fw_bk_losses.append(L)

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

plt.plot(range(epochs), fw_bk_losses)

plt.title('Training Loss')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.show()

As we can see in the plot above where the loss is plotted with respect to the number of epochs the network experienced, we clearly observed a decrease of the loss. In other words, the network seems to make less and less errors. In other words, it learns something.

4.5 - Visualization of NN’s Performace for Double Circle Case

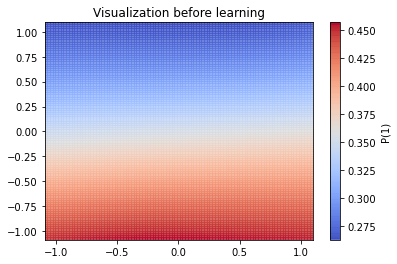

Before to see what the network learned, it would be interesting to see how the initial weights of the network would perform.

def visualization(weights, X_data, title, superposed_training=False):

N_test_points = 100 #1000

xs = np.linspace(1.1*np.min(X_data), 1.1*np.max(X_data), N_test_points)

datapoints = np.transpose([np.tile(xs, len(xs)), np.repeat(xs, len(xs))])

Y_initial = forward_propagation(datapoints, weights)[0].reshape(N_test_points, N_test_points)

X1, X2 = np.meshgrid(xs, xs)

plt.pcolormesh(X1, X2, Y_initial, cmap=plt.cm.coolwarm, alpha=0.8)

plt.colorbar(label='P(1)')

if superposed_training:

plt.scatter(X_data[:N_points//2, 0], X_data[:N_points//2, 1], s=10, color='tomato', alpha=0.5)

plt.scatter(X_data[N_points//2:, 0], X_data[N_points//2:, 1], s=10, color='cyan', alpha=0.5)

plt.title(title)

plt.show()

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

visualization(initial_weights, X, 'Visualization before learning')

The picture above represents as a colormap the probability of a point being of class 1. As expected, the network is completely unable yet to classify correctly. Let’s visualize the same thing after learning:

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

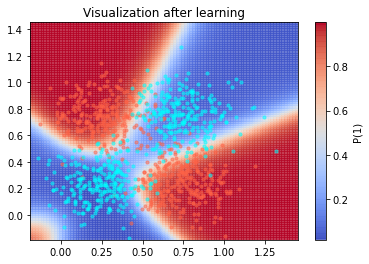

visualization(weights, X, 'Visualization after learning')

Now an island of class “1” lives in the middle of the map, while the rest is of class 0. If we superimpose the training samples to this visualization we realize that our network did a pretty good job classifying this map.

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

visualization(weights, X, 'Visualization after learning', superposed_training=True)

4.6 - Visualization of NN’s Performace for XOR Case

Let’s try our implementation with XOR like distribution.

def generate_xor_like_dataset(N_points):

# 1 class

X_class_1 = np.concatenate(

(np.concatenate(

(np.random.normal(0.25, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1),

np.random.normal(0.75, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1)),

axis=1),

np.concatenate(

(np.random.normal(0.75, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1),

np.random.normal(0.25, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1)),

axis=1))

)

Y_class_1 = np.full((N_points//2,), 1)

# 0 class

X_class_0 = np.concatenate(

(np.concatenate(

(np.random.normal(0.25, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1),

np.random.normal(0.25, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1)),

axis=1),

np.concatenate(

(np.random.normal(0.75, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1),

np.random.normal(0.75, 0.15, size=N_points//4).reshape(N_points//4,1)),

axis=1))

)

Y_class_0 = np.full((N_points//2,), 0)

X = np.concatenate((X_class_1, X_class_0), axis=0)

Y = np.concatenate((Y_class_1, Y_class_0), axis=0)

return X, Y

xor_X, xor_Y = generate_xor_like_dataset(N_points)

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

plt.scatter(xor_X[:N_points//2, 0], xor_X[:N_points//2, 1], s=10,color='red', label='class 1',alpha=0.5)

plt.scatter(xor_X[N_points//2:, 0], xor_X[N_points//2:, 1], s=10,color='blue', label='class 0',alpha=0.5)

plt.legend(loc=9, bbox_to_anchor=(0.5, -0.1), ncol=2)

plt.show()

xor_weights = {

'W1': np.random.randn(3, 2),

'b1': np.zeros(3),

'W2': np.random.randn(3),

'b2': 0,

}

xor_initial_weights = copy.deepcopy(xor_weights)

xor_losses = []

for epoch in range(epochs):

gradients, L = back_propagation(xor_X, xor_Y, xor_weights)

for weight_name in xor_weights:

xor_weights[weight_name] -= epsilon * gradients[weight_name]

xor_losses.append(L)

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

plt.plot(range(epochs), xor_losses)

plt.title('Training Loss')

plt.xlabel('Epoch')

plt.ylabel('Loss')

plt.show()

fig,ax=plt.subplots(1,1,figsize=(6,4))

visualization(xor_weights, xor_X, 'Visualization after learning', superposed_training=True)

5 - Conclusion

Back-propagation is not an extremely complicated algorithm, but with numerical approach, it still requests tendendous amount of tedious computation; it become computationally more difficult as we have more hidden layers. Introducing back-propagation helps to mitigate such issue.

Leave a comment