Regular Expression Tutorial

1. Introduction

Regular expressions are Python’s method to check some patterns in your program.

# ignore errors

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings(action='ignore')

# 1. magic to print version

# 2. magic so that the notebook will reload external python modules

# https://gist.github.com/minrk/3301035

%load_ext watermark

%load_ext autoreload

%autoreload

import pandas as pd

import re

%watermark -a 'Jae H. Choi' -d -t -v -p pandas,re

Jae H. Choi 2020-08-21 13:57:39

CPython 3.8.3

IPython 7.16.1

pandas 1.0.5

re 2.2.1

2. The Simple Patterns

The pattern is a string preceded by the r, which tells Python to interpet the string (the pattern that you want to see) as a regular expression. If you want to see if a variable pattern it in a word, find_eat() would help

def find_it(word):

found = re.search(r'it', word)

if found:

print(word, ': found the pattern of "it".')

else:

print(word, ': NO the pattern of "it".')

############# Check #############

find_it('this')

find_it('is')

find_it('fitting')

find_it('good')

this : NO the pattern of "it".

is : NO the pattern of "it".

fitting : found the pattern of "it".

good : NO the pattern of "it".

3. Matching any single character

What if a pattern that will match the letter e followed by any character at all, followed by the letter t. (e.g. e_t like ‘eat’er, b’ett’er, etc.) To say “any character at all”, use .. Here’s the pattern:

NOTE any character can be inserted to _

def finder(pattern, word):

found = re.search(pattern, word)

if found:

print(word, f': Found the pattern.')

else:

print(word, f': No pattern.')

############# Check #############

finder(r'e.t', 'better')

finder(r'e.t', 'either')

finder(r'e.t', 'best')

finder(r'e.t', 'beast')

finder(r'e.t', 'etch')

finder(r'e.t', 'ease')

better : Found the pattern.

either : Found the pattern.

best : Found the pattern.

beast : No pattern.

etch : No pattern.

ease : No pattern.

4. Matching classes of characters

Now let’s find out how to narrow down the field a bit. We’d like to be able to find a pattern starting letter b, followed by any vowel (a, e, i, o, or u), followed by letter t (e.g. b_t like bot, bat, bite). To say “any one of a certain series of characters”, you enclose them in square brackets. The finder() found patters in words like bat, bet, rabbit, robotic, and abutment

NOTE any vowel can be inserted to _

############# Check #############

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'bot')

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'bat')

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'rabbit')

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'robotic')

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'abutment')

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'boot')

finder(r'b[aeiou]t', 'beautiful')

bot : Found the pattern.

bat : Found the pattern.

rabbit : Found the pattern.

robotic : Found the pattern.

abutment : Found the pattern.

boot : No pattern.

beautiful : No pattern.

You may also complement (negate ^ inside of the bracket) a class. The following patterns are examples:

r'e[^aeiou]t': letter e followed by anything except a vowel, followed by a letter t e.g. e_tr'[^A-Z]': any character except a capital letter

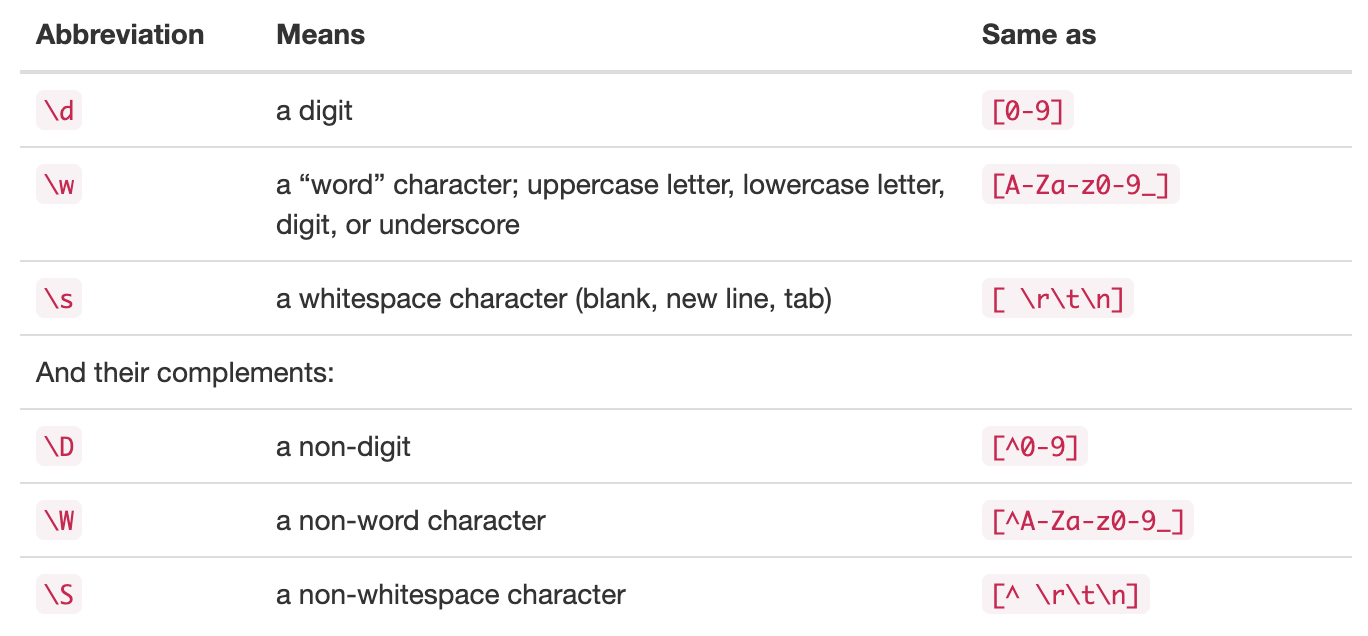

Likewise, there are some classes that are so useful that Python provides quick and easy abbrevations:

5. Anchors

All the patterns youe’ve seen so far will find a match anywhere within a string. But, what if you need to find the word go only at the beginning of a word like gone, not forgot? To solve such an issue, Anchor comes; make sure that you are at a certain boundary before you continue the match. Unlike character classes, which match individual characters in a string, these anchors do not match any character; they simply establish that you are on the correct boundaries.

The ^ outside of a bracket matches the beginning of a line, and the $ matches the end of a line. Thus, ^[A-Z] matches a capital letter at the beginning of the line.

Note that if you put the ^ inside of the bracket, you are using negation.

The \b and \B are stand for a “word boundary” and “non-word boundary” respectively. For example, if you want to find the word met at the beginning of a word, we write the pattern r'\bmet', which will match like metal or metropolitan, not helmet. The pattern r'ing\b' will match like Hiking or writing, not ingots. Finally,the pattern r'\bhat\b' matches only like hat, not That or haters.

def find_boundary(in_str):

found1 = re.search(r'\bmeet', in_str)

found2 = re.search(r'ing\b', in_str)

found3 = re.search(r'\bhat\b', in_str)

if found1:

print(f'"{in_str}" : Found "meet" at the start of a word.')

if found2:

print(f'"{in_str}" : Found "ing" at the end of a word.')

if found3:

print(f'"{in_str}" : Found word "hat" in it.')

############# Check #############

in_str = input('Enter one of the preceding sentences:')

find_boundary(in_str)

Enter one of the preceding sentences: Are we meeting here? That is amazing!

"Are we meeting here? That is amazing!" : Found "meet" at the start of a word.

"Are we meeting here? That is amazing!" : Found "ing" at the end of a word.

While \b is used to find the breakpoint between words and non-words, \B finds pairs of letters or nonletters.

6. Repetition

What if we want to match three digits in a row, or an arbitrary number of vowels? You can follow any class or character by a repetition count:

For instance, your ssn pattern match like r'\d{3}-\d{2}-\d{4}. There are three repetitions that are so common that Python has special symbols for them: * means “zero or more,” + means “one or more,” and ? means “zero or one.” Thus, if you want to look for lines consisting of last names followed by a first initial, you could use this pattern:

def find_last_and_initial(in_str):

# (word 1 or more)(, 0 or 1)(space)(A-Z 0 or more)

found = re.search(r'^\w+,?\s*[A-Z]$', in_str)

if found:

print(in_str, ': Found the pattern.')

else:

print(in_str, ': NO such pattern.')

############# Check #############

find_last_and_initial('Jae, C')

find_last_and_initial('Erik Naylor')

find_last_and_initial('Jae C')

find_last_and_initial('Tanyon')

Jae, C : Found the pattern.

Erik Naylor : NO such pattern.

Jae C : Found the pattern.

Tanyon : NO such pattern.

Let’s analyze that pattern by parts:

^starting at the beginning of the string\w+look for one or more word characters,?followed by an optional comma (zero or one commas)\s*zero or more spaces[A-Z]and a capital letter$which must be at the end of the string

7. Grouping

What if you want to scan for a last name, followed by an optional comma-whitespace-initial; it find name in both cases like ‘Smith, J’ or ‘Smith’?

def valid_name(in_str):

# (word 1 or more)(, 0 or 1)(space)(A-Z 0 or more)

found = re.search(r'^\w+(,?\s*[A-Z])?$', in_str)

if found:

print(in_str, ': Found the pattern.')

else:

print(in_str, ': No such pattern.')

############# Check #############

valid_name('Jae, C')

valid_name('Erik')

valid_name('Calvin K')

valid_name('Big Mouth')

Jae, C : Found the pattern.

Erik : Found the pattern.

Calvin K : Found the pattern.

Big Mouth : No such pattern.

8. Modifiers

If you want a pattern match to be case-insenstive, add the flags=re.I to the search() call (The I stands for IGNORECASE, which you may also spell out completely if you wish). The following example shows a pattern that will match any Canadian postal code in upper or lower case. Canadian postal codes consist of a letter, a digit, and another letter, followed by a space, a digit, a letter, and another digit. An example of a valid postal code would be A5B 6R9.

def valid_postcode_ignore(in_str):

# (start with A-Z 1)(digit 1)(A-Z 1)(space)(digit 1)(A-Z 1)(digit 1)

found = re.search(r'^[A-Z]\d[A-Z]\s+\d[A-Z]\d$', in_str, flags=re.I)

if found:

print(in_str, ': Found the pattern.')

else:

print(in_str, ': No such pattern.')

def valid_postcode_noig(in_str):

# (start with A-Z 1)(digit 1)(A-Z 1)(space)(digit 1)(A-Z 1)(digit 1)

found = re.search(r'^[A-Z]\d[A-Z]\s+\d[A-Z]\d$', in_str)

if found:

print(in_str, ': Found the pattern.')

else:

print(in_str, ': No such pattern.')

############# Check #############

valid_postcode_ignore('A5B 6R9')

valid_postcode_ignore('c7H 8j2')

# ignore vs. without ignore

valid_postcode_noig('c7H 8j2')

A5B 6R9 : Found the pattern.

c7H 8j2 : Found the pattern.

c7H 8j2 : No such pattern.

9. Advanced Pattern Matching

All you have done so far is testing to see whether a pattern matches or not. Now that you can match a person’s last name and initial, you might want to be able to grab them out of the string so that you can change ‘Martinez, A’ to ‘A. Martinez’. To accomplish this, you will need something other than search(); you will need the sub() method to do substitution. You will also have to use the grouping parentheses, which have a side effect: whenever you use parentheses to group something, the pattern matching operation stores the part of the string that matched the group so that you can use it later on.

It is now time to reveal a secret: the return value from search() is not a boolean; it is a matching object that has special properties that you can examine and use. In the following example, we have put parentheses around the ‘last name’ part of the pattern as well as the ‘comma and initial’ part. If there is a match, the program will display whatever was found in the grouping parentheses. The vertical bars are in the print() so that you can see where there are blanks (if any).

def valid_name(in_str):

found = re.search(r'^(\w+)(,?\s*[A-Z])?$', in_str)

if found:

print('Pattern match results:')

print('whole match: |', found.group(0), '|', sep='')

print('first set of (): |', found.group(1), '|', sep='')

print('second set of (): |', found.group(2), '|', sep='')

else:

print(in_str, 'does not contain the pattern.')

valid_name('Jae, C')

# valid_name('Erik') # try uncommenting these as well

Pattern match results:

whole match: |Jae, C|

first set of (): |Jae|

second set of (): |, C|

In the preceding code, found is the match object produced by the search() method. The found.group(0) method calls contains everything matched by the entire pattern. found.group(1) contains the part of the string that the first set of grouping parentheses matched–the last name, and found.group(2) contains the part of the string matched by the second set of grouping parentheses–the comma and initial, if any. If the pattern had more groups of parentheses, you would use .group(3), .group(4), and so forth.

If you look at the output from Jae, C you’ll see that the second set of grouping parentheses doesn’t give you quite what you want. The group stores the entire matched substring, which includes the comma. You’d like to store only the initial. You can do this two ways. First, you can include yet another set of parentheses:

def valid_name(in_str):

found = re.search(r'^(\w+)(,?\s*([A-Z]))?$', in_str)

if found:

print('Pattern match results:')

print('whole match: |', found.group(0), '|', sep='')

print('first set of (): |', found.group(1), '|', sep='')

print('outer set of (): |', found.group(2), '|', sep='')

print('inner set of (): |', found.group(3), '|', sep='')

else:

print(in_str, 'does not contain the pattern.')

valid_name('Jae, C')

Pattern match results:

whole match: |Jae, C|

first set of (): |Jae|

outer set of (): |, C|

inner set of (): |C|

If you do it this way, then the capital letter is stored in found.group(3) and the entire comma-and-initial is stored in found.group(2).

The other way to do this is to say that the outer parentheses should group but not store the matched portion in the result array. You do that with a question mark and colon right after the outer parentheses.

def valid_name(in_str):

found = re.search(r'^(\w+)(?:,?\s*([A-Z]))?$', in_str)

if found:

print('Pattern match results:')

print('whole match: |', found.group(0), '|', sep='')

print('first set of (): |', found.group(1), '|', sep='')

print('inner set of (): |', found.group(2), '|', sep='')

else:

print(in_str, 'does not contain the pattern.')

valid_name('Jae, C')

Pattern match results:

whole match: |Jae, C|

first set of (): |Jae|

inner set of (): |C|

In this case, the initial is in found.group(2), since the outer set of open parentheses doesn’t get stored. As you can see, patterns can very quickly become difficult to read, so let’s break this into parts:

^at the start of the string,(\w+)look for (and remember) one or more “word” characters(?:start a non-storing group which consists of:,?an optional comma\s*zero or more spaces([A-Z])and a capital letter, which is remembered because it is in parentheses

)?this ends the non-storing group; the question mark means it is all optional$at which point we must be at the end of the string.

Now that you know how to extract the last name and initial, you are in a position to use sub() to swap their positions. The re.sub() method takes three arguments:

- A pattern to search for

- A replacement pattern

- The string to search in

So, re.sub(r'-\d{4}', r'-XXXX', '301-22-0109') will replace the last four digits of a Social Security number by Xes. This example does not work in ActiveCode (since re.sub() is not implemented), but it will work in IDLE.

If you are using grouping, you can use \1 and \2 in the replacement pattern to stand for the first and second matched groups. This is how you can write a program that will change names like “Jae, C” to “C. Jae”; in the following example, the comma and initial are not optional.

def swap_name(in_str):

result = re.sub(r'^(\w+),?\s*([A-Z])$', r'\2. \1', in_str )

return result

print(swap_name('Smith, J'))

print(swap_name('Joe-Bob Smythe-Fauntleroy'))

print(swap_name('Madonna'))

print(swap_name('Gonzales M'))

J. Smith

Joe-Bob Smythe-Fauntleroy

Madonna

M. Gonzales

If you run the preceding program in IDLE, you will see that if the pattern does not match, re.sub() returns a copy of the input string, untouched..

Finally, another example with groups. Say you want to match a phone number and find the area code, prefix, and number. In this case, rather than doing a substitution, we return a list with the relevant information, or a list of three empty strings if the input is not valid. Note that when you want to match to a real parenthesis, you have to precede it with a backslash to make it “not part of a group.” You can do it this way:

Again, let’s break apart that pattern:

\(look for a real open parenthesis(\d{3})followed by three digits (and store them)\)and a real closing parenthesis\s*followed by zero or more spaces- (\d{3}) three digits (store them)

-a dash(\d{4})and four more digits (store them)

10. Finding All Occurrences

The re.search() method finds only the first occurrence of a pattern within a string. If you want to find all the matches in a string, use re.findall(), which returns a list of matched substrings. (Unlike re.search(), which returns match objects.) Here is a pattern that finds a capital letter followed by an optional dash and a single digit:

message = 'Insert tabs B3, D-7, and C6 into slot A9.'

result = re.findall(r'([A-Z]-?\d)', message)

if result:

for item in result:

print(item)

else:

print('findall() did not find any matches to the pattern.')

B3

D-7

C6

A9

Please check the source

Leave a comment