Deep Learning Performance Improvement 3 - Regularization

Regularization

Regularization is used for a model to predict better. For Deep Learning models, overfitting commonly happens if the training dataset is not big enough so penalizing technique (L1 called LASSO and L2 called Ridge) and dropout technique will be introduced. Then such overfitting problem like predicting well on a training dataset, but not predicting well on a testing dataset can be fixed.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns; sns.set_style("whitegrid")

%matplotlib inline

# from reg_utils import sigmoid, relu, plot_decision_boundary, initialize_parameters, load_2D_dataset, predict_dec

# from reg_utils import compute_cost, predict, forward_propagation, backward_propagation, update_parameters

import sklearn

import sklearn.datasets

import scipy.io

from testCases import *

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (7.0, 4.0) # set default size of plots

plt.rcParams['image.interpolation'] = 'nearest'

plt.rcParams['image.cmap'] = 'gray'

def sigmoid(x):

"""

Compute the sigmoid of x

Arguments:

x -- A scalar or numpy array of any size.

Return:

s -- sigmoid(x)

"""

s = 1/(1+np.exp(-x))

return s

def relu(x):

"""

Compute the relu of x

Arguments:

x -- A scalar or numpy array of any size.

Return:

s -- relu(x)

"""

s = np.maximum(0,x)

return s

def forward_propagation(X, parameters):

"""

Implements the forward propagation (and computes the loss) presented in Figure 2.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (input size, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (containing 0 if cat, 1 if non-cat)

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", "W2", "b2", "W3", "b3":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape ()

b1 -- bias vector of shape ()

W2 -- weight matrix of shape ()

b2 -- bias vector of shape ()

W3 -- weight matrix of shape ()

b3 -- bias vector of shape ()

Returns:

loss -- the loss function (vanilla logistic loss)

"""

# retrieve parameters

W1 = parameters["W1"]

b1 = parameters["b1"]

W2 = parameters["W2"]

b2 = parameters["b2"]

W3 = parameters["W3"]

b3 = parameters["b3"]

# LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> SIGMOID

z1 = np.dot(W1, X) + b1

a1 = relu(z1)

z2 = np.dot(W2, a1) + b2

a2 = relu(z2)

z3 = np.dot(W3, a2) + b3

a3 = sigmoid(z3)

cache = (z1, a1, W1, b1, z2, a2, W2, b2, z3, a3, W3, b3)

return a3, cache

def backward_propagation(X, Y, cache):

"""

Implement the backward propagation presented in figure 2.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (input size, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (containing 0 if cat, 1 if non-cat)

cache -- cache output from forward_propagation()

Returns:

gradients -- A dictionary with the gradients with respect to each parameter, activation and pre-activation variables

"""

m = X.shape[1]

(z1, a1, W1, b1, z2, a2, W2, b2, z3, a3, W3, b3) = cache

dz3 = 1./m * (a3 - Y)

dW3 = np.dot(dz3, a2.T)

db3 = np.sum(dz3, axis=1, keepdims = True)

da2 = np.dot(W3.T, dz3)

dz2 = np.multiply(da2, np.int64(a2 > 0))

dW2 = np.dot(dz2, a1.T)

db2 = np.sum(dz2, axis=1, keepdims = True)

da1 = np.dot(W2.T, dz2)

dz1 = np.multiply(da1, np.int64(a1 > 0))

dW1 = np.dot(dz1, X.T)

db1 = np.sum(dz1, axis=1, keepdims = True)

gradients = {"dz3": dz3, "dW3": dW3, "db3": db3,

"da2": da2, "dz2": dz2, "dW2": dW2, "db2": db2,

"da1": da1, "dz1": dz1, "dW1": dW1, "db1": db1}

return gradients

def update_parameters(parameters, grads, learning_rate):

"""

Update parameters using gradient descent

Arguments:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters

grads -- python dictionary containing your gradients, output of n_model_backward

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your updated parameters

parameters['W' + str(i)] = ...

parameters['b' + str(i)] = ...

"""

L = len(parameters) // 2 # number of layers in the neural networks

# Update rule for each parameter

for k in range(L):

parameters["W" + str(k+1)] = parameters["W" + str(k+1)] - learning_rate * grads["dW" + str(k+1)]

parameters["b" + str(k+1)] = parameters["b" + str(k+1)] - learning_rate * grads["db" + str(k+1)]

return parameters

def compute_loss(a3, Y):

"""

Implement the loss function

Arguments:

a3 -- post-activation, output of forward propagation

Y -- "true" labels vector, same shape as a3

Returns:

loss - value of the loss function

"""

m = Y.shape[1]

logprobs = np.multiply(-np.log(a3),Y) + np.multiply(-np.log(1 - a3), 1 - Y)

loss = 1./m * np.nansum(logprobs)

return loss

def load_cat_dataset():

train_dataset = h5py.File('datasets/train_catvnoncat.h5', "r")

train_set_x_orig = np.array(train_dataset["train_set_x"][:]) # your train set features

train_set_y_orig = np.array(train_dataset["train_set_y"][:]) # your train set labels

test_dataset = h5py.File('datasets/test_catvnoncat.h5', "r")

test_set_x_orig = np.array(test_dataset["test_set_x"][:]) # your test set features

test_set_y_orig = np.array(test_dataset["test_set_y"][:]) # your test set labels

classes = np.array(test_dataset["list_classes"][:]) # the list of classes

train_set_y = train_set_y_orig.reshape((1, train_set_y_orig.shape[0]))

test_set_y = test_set_y_orig.reshape((1, test_set_y_orig.shape[0]))

train_set_x_orig = train_set_x_orig.reshape(train_set_x_orig.shape[0], -1).T

test_set_x_orig = test_set_x_orig.reshape(test_set_x_orig.shape[0], -1).T

train_set_x = train_set_x_orig/255

test_set_x = test_set_x_orig/255

return train_set_x, train_set_y, test_set_x, test_set_y, classes

def predict(X, y, parameters):

"""

This function is used to predict the results of a n-layer neural network.

Arguments:

X -- data set of examples you would like to label

parameters -- parameters of the trained model

Returns:

p -- predictions for the given dataset X

"""

m = X.shape[1]

p = np.zeros((1,m), dtype = np.int)

# Forward propagation

a3, caches = forward_propagation(X, parameters)

# convert probas to 0/1 predictions

for i in range(0, a3.shape[1]):

if a3[0,i] > 0.5:

p[0,i] = 1

else:

p[0,i] = 0

# print results

print("Accuracy: " + str(np.mean((p[0,:] == y[0,:]))))

return p

def plot_decision_boundary(model, X, y):

# Set min and max values and give it some padding

x_min, x_max = X[0, :].min() - 1, X[0, :].max() + 1

y_min, y_max = X[1, :].min() - 1, X[1, :].max() + 1

h = 0.01

# Generate a grid of points with distance h between them

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h), np.arange(y_min, y_max, h))

# Predict the function value for the whole grid

Z = model(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()])

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)

# Plot the contour and training examples

plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, cmap=plt.cm.coolwarm, alpha=0.3)

plt.ylabel('x2')

plt.xlabel('x1')

plt.scatter(X[0, :], X[1, :], c=np.squeeze(y), cmap=plt.cm.coolwarm, s=10, alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

def predict_dec(parameters, X):

"""

Used for plotting decision boundary.

Arguments:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters

X -- input data of size (m, K)

Returns

predictions -- vector of predictions of our model (red: 0 / blue: 1)

"""

# Predict using forward propagation and a classification threshold of 0.5

a3, cache = forward_propagation(X, parameters)

predictions = (a3>0.5)

return predictions

def initialize_parameters(layer_dims):

"""

Arguments:

layer_dims -- python array (list) containing the dimensions of each layer in our network

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", ..., "WL", "bL":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape (layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1])

b1 -- bias vector of shape (layer_dims[l], 1)

Wl -- weight matrix of shape (layer_dims[l-1], layer_dims[l])

bl -- bias vector of shape (1, layer_dims[l])

Tips:

- For example: the layer_dims for the "Planar Data classification model" would have been [2,2,1].

This means W1's shape was (2,2), b1 was (1,2), W2 was (2,1) and b2 was (1,1). Now you have to generalize it!

- In the for loop, use parameters['W' + str(l)] to access Wl, where l is the iterative integer.

"""

np.random.seed(3)

parameters = {}

L = len(layer_dims) # number of layers in the network

for l in range(1, L):

parameters['W' + str(l)] = np.random.randn(layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1]) / np.sqrt(layer_dims[l-1])

parameters['b' + str(l)] = np.zeros((layer_dims[l], 1))

assert(parameters['W' + str(l)].shape == layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1])

assert(parameters['W' + str(l)].shape == layer_dims[l], 1)

return parameters

def compute_cost(a3, Y):

"""

Implement the cost function

Arguments:

a3 -- post-activation, output of forward propagation

Y -- "true" labels vector, same shape as a3

Returns:

cost - value of the cost function

"""

m = Y.shape[1]

logprobs = np.multiply(-np.log(a3),Y) + np.multiply(-np.log(1 - a3), 1 - Y)

cost = 1./m * np.nansum(logprobs)

return cost

def load_2D_dataset():

data = scipy.io.loadmat('datasets/data.mat')

train_X = data['X'].T

train_Y = data['y'].T

test_X = data['Xval'].T

test_Y = data['yval'].T

plt.scatter(train_X[0, :], train_X[1, :], c=train_Y, s=10, cmap=plt.cm.coolwarm, alpha=0.5);

return train_X, train_Y, test_X, test_Y

<>:257: SyntaxWarning: assertion is always true, perhaps remove parentheses?

<>:258: SyntaxWarning: assertion is always true, perhaps remove parentheses?

<>:257: SyntaxWarning: assertion is always true, perhaps remove parentheses?

<>:258: SyntaxWarning: assertion is always true, perhaps remove parentheses?

<ipython-input-6-e9e79aba8c99>:257: SyntaxWarning: assertion is always true, perhaps remove parentheses?

assert(parameters['W' + str(l)].shape == layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1])

<ipython-input-6-e9e79aba8c99>:258: SyntaxWarning: assertion is always true, perhaps remove parentheses?

assert(parameters['W' + str(l)].shape == layer_dims[l], 1)

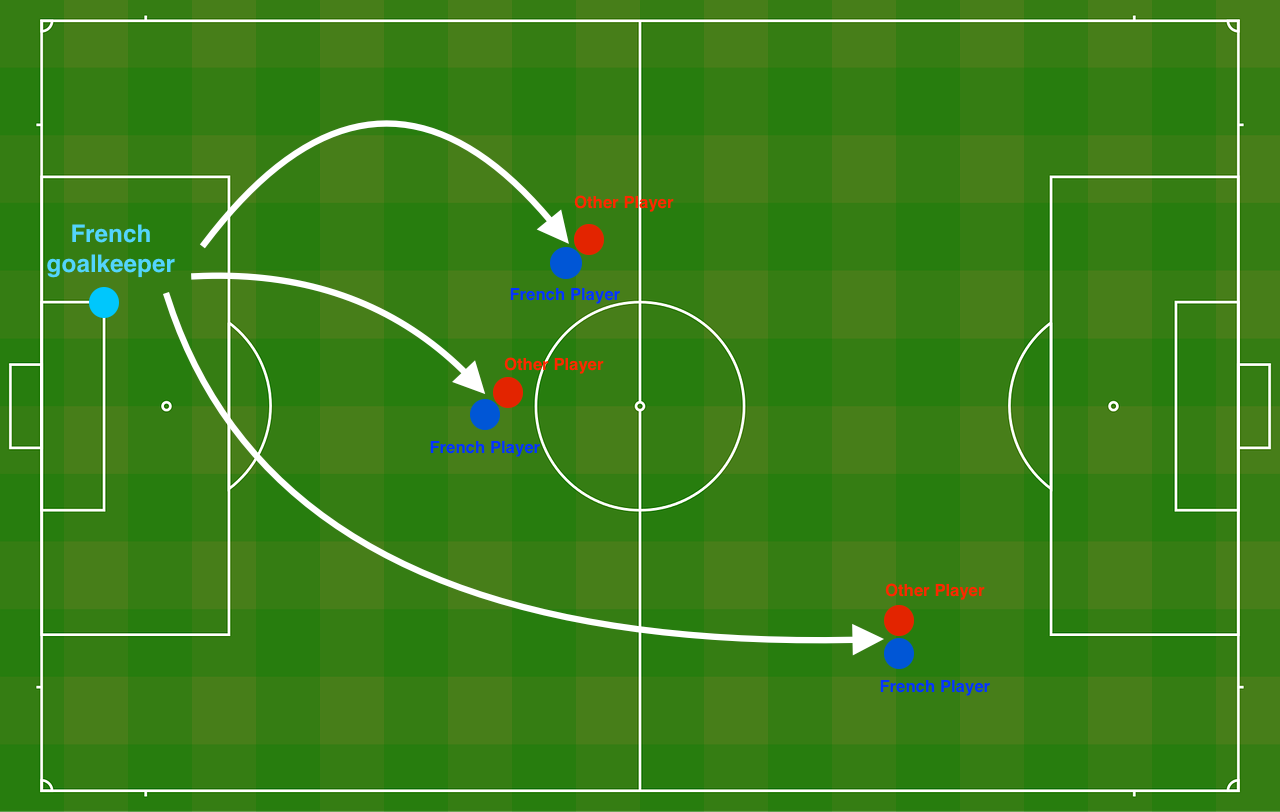

Problem Statement: You have just been hired as an AI expert by the French Football Corporation. They would like you to recommend positions where France’s goal keeper should kick the ball so that the French team’s players can then hit it with their head.

As Figure 1 shows, the goal keeper kicks the ball in the air, the players of each team are fighting to hit the ball with their head.

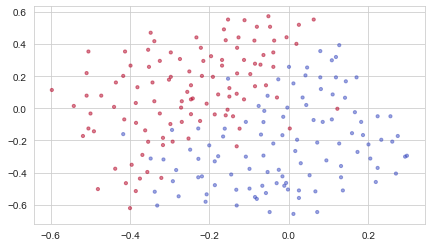

They give you the following 2D dataset from France’s past 10 games.

train_X, train_Y, test_X, test_Y = load_2D_dataset()

Each dot corresponds to a position on the football field where a football player has hit the ball with his/her head after the French goal keeper has shot the ball from the left side of the football field.

- If the dot is blue, it means the French player managed to hit the ball with his/her head

- If the dot is red, it means the other team’s player hit the ball with their head

Your goal: Use a deep learning model to find the positions on the field where the goalkeeper should kick the ball.

Analysis of the dataset: This dataset is a little noisy, but it looks like a diagonal line separating the upper left half (blue) from the lower right half (red) would work well.

You will first try a non-regularized model. Then you’ll learn how to regularize it and decide which model you will choose to solve the French Football Corporation’s problem.

1 - Non-regularized model

You will use the following neural network (already implemented for you below). This model can be used:

- in regularization mode – by setting the

lambdinput to a non-zero value. We use “lambd” instead of “lambda” because “lambda” is a reserved keyword in Python. - in dropout mode – by setting the

keep_probto a value less than one

You will first try the model without any regularization. Then, you will implement:

- L2 regularization – functions: “

compute_cost_with_regularization()” and “backward_propagation_with_regularization()” - Dropout – functions: “

forward_propagation_with_dropout()” and “backward_propagation_with_dropout()”

In each part, you will run this model with the correct inputs so that it calls the functions you’ve implemented. Take a look at the code below to familiarize yourself with the model.

def model(X, Y, learning_rate = 0.3, num_iterations = 30000, print_cost = True, lambd = 0, keep_prob = 1):

"""

Implements a three-layer neural network: LINEAR->RELU->LINEAR->RELU->LINEAR->SIGMOID.

Arguments:

X -- input data, of shape (input size, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (1 for blue dot / 0 for red dot), of shape (output size, number of examples)

learning_rate -- learning rate of the optimization

num_iterations -- number of iterations of the optimization loop

print_cost -- If True, print the cost every 10000 iterations

lambd -- regularization hyperparameter, scalar

keep_prob - probability of keeping a neuron active during drop-out, scalar.

Returns:

parameters -- parameters learned by the model. They can then be used to predict.

"""

grads = {}

costs = [] # to keep track of the cost

m = X.shape[1] # number of examples

layers_dims = [X.shape[0], 20, 3, 1]

# Initialize parameters dictionary.

parameters = initialize_parameters(layers_dims)

# Loop (gradient descent)

for i in range(0, num_iterations):

# Forward propagation: LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> SIGMOID.

if keep_prob == 1:

a3, cache = forward_propagation(X, parameters)

elif keep_prob < 1:

a3, cache = forward_propagation_with_dropout(X, parameters, keep_prob)

# Cost function

if lambd == 0:

cost = compute_cost(a3, Y)

else:

cost = compute_cost_with_regularization(a3, Y, parameters, lambd)

# Backward propagation.

assert(lambd == 0 or keep_prob == 1) # it is possible to use both L2 regularization and dropout,

# but this assignment will only explore one at a time

if lambd == 0 and keep_prob == 1:

grads = backward_propagation(X, Y, cache)

elif lambd != 0:

grads = backward_propagation_with_regularization(X, Y, cache, lambd)

elif keep_prob < 1:

grads = backward_propagation_with_dropout(X, Y, cache, keep_prob)

# Update parameters.

parameters = update_parameters(parameters, grads, learning_rate)

# Print the loss every 10000 iterations

if print_cost and i % 10000 == 0:

print("Cost after iteration {}: {}".format(i, cost))

if print_cost and i % 1000 == 0:

costs.append(cost)

# plot the cost

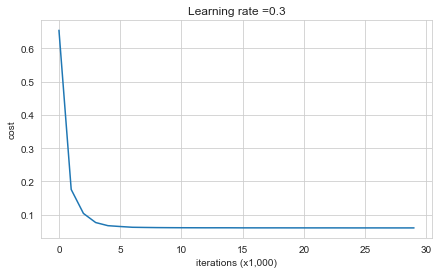

plt.plot(costs)

plt.ylabel('cost')

plt.xlabel('iterations (x1,000)')

plt.title("Learning rate =" + str(learning_rate))

plt.show()

return parameters

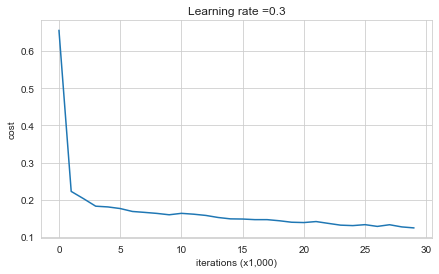

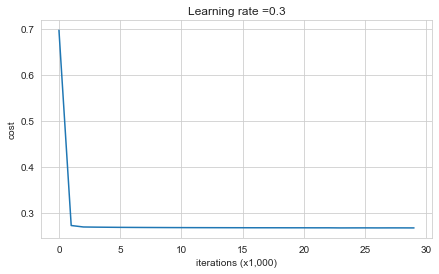

Let’s train the model without any regularization, and observe the accuracy on the train/test sets.

parameters = model(train_X, train_Y)

print("On the training set:")

predictions_train = predict(train_X, train_Y, parameters)

print("On the test set:")

predictions_test = predict(test_X, test_Y, parameters)

Cost after iteration 0: 0.6557412523481002

Cost after iteration 10000: 0.16329987525724218

Cost after iteration 20000: 0.13851642423264765

On the training set:

Accuracy: 0.9478672985781991

On the test set:

Accuracy: 0.915

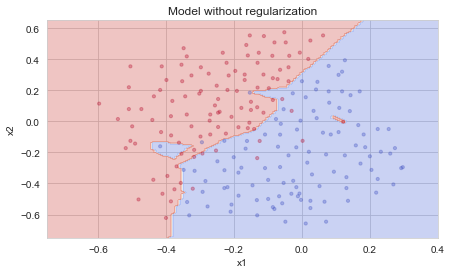

The train accuracy is 94.8% while the test accuracy is 91.5%. This is the baseline model (you will observe the impact of regularization on this model). Run the following code to plot the decision boundary of your model.

plt.title("Model without regularization")

axes = plt.gca()

axes.set_xlim([-0.75, 0.40])

axes.set_ylim([-0.75, 0.65])

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict_dec(parameters, x.T), train_X, train_Y)

The non-regularized model is obviously overfitting the training set. It is fitting the noisy points! Lets now look at two techniques to reduce overfitting.

2 - Penalizing Regularization (L2)

When training is proceded, a model is prune to overfit (high variance). High variance means that your model learned from all noise and errors (like outliers) in the data. To generalize the trend with ignoring noise ‘well’, the idea of controlling complexity of model is based here; to penalize the complexity instead of computing the cost (loss). By thinking of variance-bias tradeoff, penlalizing regularization prevents high variance.

- L1 (LASSO) uses absolute weights: it causes sparse outputs.

- L2 (Ridge) uses square of weights: it causes non-sparse outputs.

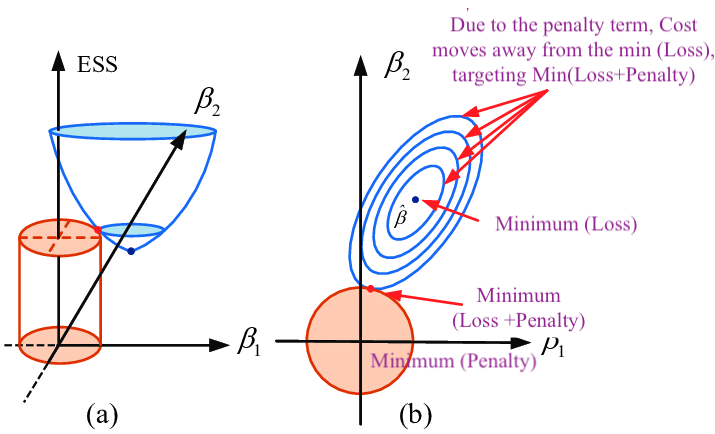

As Figure 2 shows, \(Loss(β)+λΣ(β^2)\) where \(β\) represents weight \(W\), \(λ\) determines size of penalty term. \(\lambda\) shifts the loss function (bowl shape) up to prevent model from achieving the global minimum of loss function (overfitting in this case).

L2 regularization consists of appropriately modifying your cost function, from: \(J = -\frac{1}{m} \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{m} \large{(}\small y^{(i)}\log\left(a^{[L](i)}\right) + (1-y^{(i)})\log\left(1- a^{[L](i)}\right) \large{)} \tag{1}\) To: \(J_{regularized} = \small \underbrace{-\frac{1}{m} \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{m} \large{(}\small y^{(i)}\log\left(a^{[L](i)}\right) + (1-y^{(i)})\log\left(1- a^{[L](i)}\right) \large{)} }_\text{cross-entropy cost} + \underbrace{\frac{1}{m} \frac{\lambda}{2} \sum\limits_l\sum\limits_k\sum\limits_j W_{k,j}^{[l]2} }_\text{L2 regularization cost} \tag{2}\)

Let’s modify your cost and observe the consequences.

Exercise: Implement compute_cost_with_regularization() which computes the cost given by formula (2). To calculate \(\sum\limits_k\sum\limits_j W_{k,j}^{[l]2}\) , use :

np.sum(np.square(Wl))

Note that you have to do this for \(W^{[1]}\), \(W^{[2]}\) and \(W^{[3]}\), then sum the three terms and multiply by \(\frac{1}{m} \frac{\lambda}{2}\).

# GRADED FUNCTION: compute_cost_with_regularization

def compute_cost_with_regularization(A3, Y, parameters, lambd):

"""

Implement the cost function with L2 regularization. See formula (2) above.

Arguments:

A3 -- post-activation, output of forward propagation, of shape (output size, number of examples)

Y -- "true" labels vector, of shape (output size, number of examples)

parameters -- python dictionary containing parameters of the model

Returns:

cost - value of the regularized loss function (formula (2))

"""

m = Y.shape[1]

W1 = parameters["W1"]

W2 = parameters["W2"]

W3 = parameters["W3"]

cross_entropy_cost = compute_cost(A3, Y) # This gives you the cross-entropy part of the cost

### START CODE HERE ### (approx. 1 line)

L2_regularization_cost = lambd * (np.sum(np.square(W1)) + np.sum(np.square(W2)) + np.sum(np.square(W3))) / (2 * m)

### END CODER HERE ###

cost = cross_entropy_cost + L2_regularization_cost

return cost

A3, Y_assess, parameters = compute_cost_with_regularization_test_case()

print("cost = " + str(compute_cost_with_regularization(A3, Y_assess, parameters, lambd = 0.1)))

cost = 1.7864859451590758

Expected Output:

| cost |

|---|

| 1.78648594516 |

Of course, because you changed the cost, you have to change backward propagation as well! All the gradients have to be computed with respect to this new cost.

Exercise: Implement the changes needed in backward propagation to take into account regularization. The changes only concern dW1, dW2 and dW3. For each, you have to add the regularization term’s gradient (\(\frac{d}{dW} ( \frac{1}{2}\frac{\lambda}{m} W^2) = \frac{\lambda}{m} W\)).

# GRADED FUNCTION: backward_propagation_with_regularization

def backward_propagation_with_regularization(X, Y, cache, lambd):

"""

Implements the backward propagation of our baseline model to which we added an L2 regularization.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (input size, number of examples)

Y -- "true" labels vector, of shape (output size, number of examples)

cache -- cache output from forward_propagation()

lambd -- regularization hyperparameter, scalar

Returns:

gradients -- A dictionary with the gradients with respect to each parameter, activation and pre-activation variables

"""

m = X.shape[1]

(Z1, A1, W1, b1, Z2, A2, W2, b2, Z3, A3, W3, b3) = cache

dZ3 = A3 - Y

### START CODE HERE ### (approx. 1 line)

dW3 = 1. / m * np.dot(dZ3, A2.T) + (lambd * W3) / m

### END CODE HERE ###

db3 = 1. / m * np.sum(dZ3, axis=1, keepdims=True)

dA2 = np.dot(W3.T, dZ3)

dZ2 = np.multiply(dA2, np.int64(A2 > 0))

### START CODE HERE ### (approx. 1 line)

dW2 = 1. / m * np.dot(dZ2, A1.T) + (lambd * W2) / m

### END CODE HERE ###

db2 = 1. / m * np.sum(dZ2, axis=1, keepdims=True)

dA1 = np.dot(W2.T, dZ2)

dZ1 = np.multiply(dA1, np.int64(A1 > 0))

### START CODE HERE ### (approx. 1 line)

dW1 = 1. / m * np.dot(dZ1, X.T) + (lambd * W1) / m

### END CODE HERE ###

db1 = 1. / m * np.sum(dZ1, axis=1, keepdims=True)

gradients = {"dZ3": dZ3, "dW3": dW3, "db3": db3, "dA2": dA2,

"dZ2": dZ2, "dW2": dW2, "db2": db2, "dA1": dA1,

"dZ1": dZ1, "dW1": dW1, "db1": db1}

return gradients

X_assess, Y_assess, cache = backward_propagation_with_regularization_test_case()

grads = backward_propagation_with_regularization(X_assess, Y_assess, cache, lambd=0.7)

print ("dW1 = " + str(grads["dW1"]))

print ("dW2 = " + str(grads["dW2"]))

print ("dW3 = " + str(grads["dW3"]))

dW1 = [[-0.25604646 0.12298827 -0.28297129]

[-0.17706303 0.34536094 -0.4410571 ]]

dW2 = [[ 0.79276486 0.85133918]

[-0.0957219 -0.01720463]

[-0.13100772 -0.03750433]]

dW3 = [[-1.77691347 -0.11832879 -0.09397446]]

Expected Output:

| **dW1** | [[-0.25604646 0.12298827 -0.28297129] [-0.17706303 0.34536094 -0.4410571 ]] |

| **dW2** | [[ 0.79276486 0.85133918] [-0.0957219 -0.01720463] [-0.13100772 -0.03750433]] |

| **dW3** | [[-1.77691347 -0.11832879 -0.09397446]] |

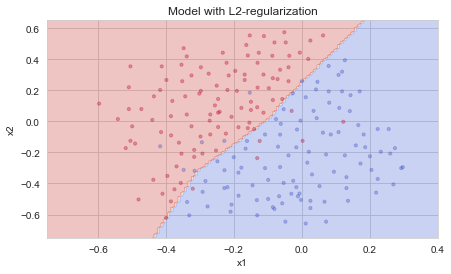

Let’s now run the model with L2 regularization \((\lambda = 0.7)\). The model() function will call:

compute_cost_with_regularizationinstead ofcompute_costbackward_propagation_with_regularizationinstead ofbackward_propagation

parameters = model(train_X, train_Y, lambd=0.7)

print("On the train set:")

predictions_train = predict(train_X, train_Y, parameters)

print("On the test set:")

predictions_test = predict(test_X, test_Y, parameters)

Cost after iteration 0: 0.6974484493131264

Cost after iteration 10000: 0.2684918873282239

Cost after iteration 20000: 0.2680916337127301

On the train set:

Accuracy: 0.9383886255924171

On the test set:

Accuracy: 0.93

Congrats, the test set accuracy increased to 93%. You have saved the French football team!

You are not overfitting the training data anymore. Let’s plot the decision boundary.

plt.title("Model with L2-regularization")

axes = plt.gca()

axes.set_xlim([-0.75,0.40])

axes.set_ylim([-0.75,0.65])

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict_dec(parameters, x.T), train_X, train_Y)

Observations:

- The value of \(\lambda\) is a hyperparameter that you can tune using a dev set.

- L2 regularization makes your decision boundary smoother. If \(\lambda\) is too large, it is also possible to “oversmooth”, resulting in a model with high bias.

What is L2-regularization actually doing?:

L2-regularization relies on the assumption that a model with small weights is simpler than a model with large weights. Thus, by penalizing the square values of the weights in the cost function you drive all the weights to smaller values. It becomes too costly for the cost to have large weights! This leads to a smoother model in which the output changes more slowly as the input changes.

**What you should remember** -- the implications of L2-regularization on:- The cost computation:

- A regularization term is added to the cost

-

The backpropagation function:

- There are extra terms in the gradients with respect to weight matrices

-

Weights end up smaller ("weight decay"):

- Weights are pushed to smaller values.

3 - Dropout

Finally, dropout is a widely used regularization technique that is specific to deep learning. It randomly shuts down some neurons in each iteration. Watch these two videos to see what this means!

As Figure 3 shows, drop-out works on the second hidden layer. At each iteration, you shut down (= set to zero) each neuron of a layer with probability \(1 - keep\_prob\) or keep it with probability \(keep\_prob\) (50% here). The dropped neurons don’t contribute to the training in both the forward and backward propagations of the iteration.

As Figure 4 shows, Drop-out on the first and third hidden layers. \(1^{st}\) layer: we shut down on average 40% of the neurons. \(3^{rd}\) layer: we shut down on average 20% of the neurons.

When you shut some neurons down, you actually modify your model. The idea behind drop-out is that at each iteration, you train a different model that uses only a subset of your neurons. With dropout, your neurons thus become less sensitive to the activation of one other specific neuron, because that other neuron might be shut down at any time.

3.1 - Forward propagation with dropout

Exercise: Implement the forward propagation with dropout. You are using a 3 layer neural network, and will add dropout to the first and second hidden layers. We will not apply dropout to the input layer or output layer.

Instructions: You would like to shut down some neurons in the first and second layers. To do that, you are going to carry out 4 Steps:

- In lecture, we dicussed creating a variable \(d^{[1]}\) with the same shape as \(a^{[1]}\) using

np.random.rand()to randomly get numbers between 0 and 1. Here, you will use a vectorized implementation, so create a random matrix \(D^{[1]} = [d^{[1](1)} d^{[1](2)} ... d^{[1](m)}]\) of the same dimension as \(A^{[1]}\). - Set each entry of \(D^{[1]}\) to be 0 with probability (

1-keep_prob) or 1 with probability (keep_prob), by thresholding values in \(D^{[1]}\) appropriately. Hint: to set all the entries of a matrix X to 0 (if entry is less than 0.5) or 1 (if entry is more than 0.5) you would do:X = (X < 0.5). Note that 0 and 1 are respectively equivalent to False and True. - Set \(A^{[1]}\) to \(A^{[1]} * D^{[1]}\). (You are shutting down some neurons). You can think of \(D^{[1]}\) as a mask, so that when it is multiplied with another matrix, it shuts down some of the values.

- Divide \(A^{[1]}\) by

keep_prob. By doing this you are assuring that the result of the cost will still have the same expected value as without drop-out. (This technique is also called inverted dropout.)

# GRADED FUNCTION: forward_propagation_with_dropout

def forward_propagation_with_dropout(X, parameters, keep_prob=0.5):

"""

Implements the forward propagation: LINEAR -> RELU + DROPOUT -> LINEAR -> RELU + DROPOUT -> LINEAR -> SIGMOID.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (2, number of examples)

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", "W2", "b2", "W3", "b3":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape (20, 2)

b1 -- bias vector of shape (20, 1)

W2 -- weight matrix of shape (3, 20)

b2 -- bias vector of shape (3, 1)

W3 -- weight matrix of shape (1, 3)

b3 -- bias vector of shape (1, 1)

keep_prob - probability of keeping a neuron active during drop-out, scalar

Returns:

A3 -- last activation value, output of the forward propagation, of shape (1,1)

cache -- tuple, information stored for computing the backward propagation

"""

np.random.seed(1)

# retrieve parameters

W1 = parameters["W1"]

b1 = parameters["b1"]

W2 = parameters["W2"]

b2 = parameters["b2"]

W3 = parameters["W3"]

b3 = parameters["b3"]

# LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> SIGMOID

Z1 = np.dot(W1, X) + b1

A1 = relu(Z1)

### START CODE HERE ### (approx. 4 lines) # Steps 1-4 below correspond to the Steps 1-4 described above.

D1 = np.random.rand(A1.shape[0], A1.shape[1]) # Step 1: initialize matrix D1 = np.random.rand(..., ...)

D1 = D1 < keep_prob # Step 2: convert entries of D1 to 0 or 1 (using keep_prob as the threshold)

A1 = A1 * D1 # Step 3: shut down some neurons of A1

A1 = A1 / keep_prob # Step 4: scale the value of neurons that haven't been shut down

### END CODE HERE ###

Z2 = np.dot(W2, A1) + b2

A2 = relu(Z2)

### START CODE HERE ### (approx. 4 lines)

D2 = np.random.rand(A2.shape[0], A2.shape[1]) # Step 1: initialize matrix D2 = np.random.rand(..., ...)

D2 = D2 < keep_prob # Step 2: convert entries of D2 to 0 or 1 (using keep_prob as the threshold)

A2 = A2 * D2 # Step 3: shut down some neurons of A2

A2 = A2 / keep_prob # Step 4: scale the value of neurons that haven't been shut down

### END CODE HERE ###

Z3 = np.dot(W3, A2) + b3

A3 = sigmoid(Z3)

cache = (Z1, D1, A1, W1, b1, Z2, D2, A2, W2, b2, Z3, A3, W3, b3)

return A3, cache

X_assess, parameters = forward_propagation_with_dropout_test_case()

A3, cache = forward_propagation_with_dropout(X_assess, parameters, keep_prob=0.7)

print ("A3 = " + str(A3))

A3 = [[0.36974721 0.00305176 0.04565099 0.49683389 0.36974721]]

Expected Output:

| A3 |

|---|

| [[ 0.36974721, 0.00305176, 0.04565099, 0.49683389, 0.36974721]] |

3.2 - Backward propagation with dropout

Exercise: Implement the backward propagation with dropout. As before, you are training a 3 layer network. Add dropout to the first and second hidden layers, using the masks \(D^{[1]}\) and \(D^{[2]}\) stored in the cache.

Instruction: Backpropagation with dropout is actually quite easy. You will have to carry out 2 Steps:

- You had previously shut down some neurons during forward propagation, by applying a mask \(D^{[1]}\) to

A1. In backpropagation, you will have to shut down the same neurons, by reapplying the same mask \(D^{[1]}\) todA1. - During forward propagation, you had divided

A1bykeep_prob. In backpropagation, you’ll therefore have to dividedA1bykeep_probagain (the calculus interpretation is that if \(A^{[1]}\) is scaled bykeep_prob, then its derivative \(dA^{[1]}\) is also scaled by the samekeep_prob).

# GRADED FUNCTION: backward_propagation_with_dropout

def backward_propagation_with_dropout(X, Y, cache, keep_prob):

"""

Implements the backward propagation of our baseline model to which we added dropout.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (2, number of examples)

Y -- "true" labels vector, of shape (output size, number of examples)

cache -- cache output from forward_propagation_with_dropout()

keep_prob - probability of keeping a neuron active during drop-out, scalar

Returns:

gradients -- A dictionary with the gradients with respect to each parameter, activation and pre-activation variables

"""

m = X.shape[1]

(Z1, D1, A1, W1, b1, Z2, D2, A2, W2, b2, Z3, A3, W3, b3) = cache

dZ3 = A3 - Y

dW3 = 1. / m * np.dot(dZ3, A2.T)

db3 = 1. / m * np.sum(dZ3, axis=1, keepdims=True)

dA2 = np.dot(W3.T, dZ3)

### START CODE HERE ### (≈ 2 lines of code)

dA2 = dA2 * D2 # Step 1: Apply mask D2 to shut down the same neurons as during the forward propagation

dA2 = dA2 / keep_prob # Step 2: Scale the value of neurons that haven't been shut down

### END CODE HERE ###

dZ2 = np.multiply(dA2, np.int64(A2 > 0))

dW2 = 1. / m * np.dot(dZ2, A1.T)

db2 = 1. / m * np.sum(dZ2, axis=1, keepdims=True)

dA1 = np.dot(W2.T, dZ2)

### START CODE HERE ### (≈ 2 lines of code)

dA1 = dA1 * D1 # Step 1: Apply mask D1 to shut down the same neurons as during the forward propagation

dA1 = dA1 / keep_prob # Step 2: Scale the value of neurons that haven't been shut down

### END CODE HERE ###

dZ1 = np.multiply(dA1, np.int64(A1 > 0))

dW1 = 1. / m * np.dot(dZ1, X.T)

db1 = 1. / m * np.sum(dZ1, axis=1, keepdims=True)

gradients = {"dZ3": dZ3, "dW3": dW3, "db3": db3,"dA2": dA2,

"dZ2": dZ2, "dW2": dW2, "db2": db2, "dA1": dA1,

"dZ1": dZ1, "dW1": dW1, "db1": db1}

return gradients

X_assess, Y_assess, cache = backward_propagation_with_dropout_test_case()

gradients = backward_propagation_with_dropout(X_assess, Y_assess, cache, keep_prob=0.8)

print ("dA1 = " + str(gradients["dA1"]))

print ("dA2 = " + str(gradients["dA2"]))

dA1 = [[ 0.36544439 0. -0.00188233 0. -0.17408748]

[ 0.65515713 0. -0.00337459 0. -0. ]]

dA2 = [[ 0.58180856 0. -0.00299679 0. -0.27715731]

[ 0. 0.53159854 -0. 0.53159854 -0.34089673]

[ 0. 0. -0.00292733 0. -0. ]]

Expected Output:

| dA1 |

|---|

| [[ 0.36544439, 0. -0.00188233, 0. -0.17408748] |

| [ 0.65515713, 0. -0.00337459, 0. -0. ]] |

| dA2 |

|---|

| [[ 0.58180856, 0. , -0.00299679, 0. -0.27715731] |

| [ 0. 0.53159854, -0. 0.53159854,-0.34089673] |

| [ 0. 0. , -0.00292733, 0. -0. ]] |

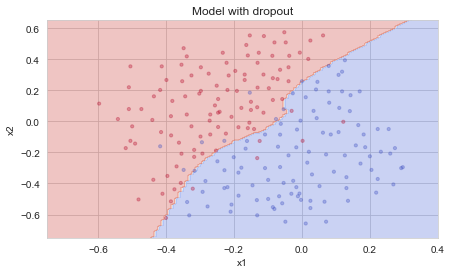

Let’s now run the model with dropout (keep_prob = 0.86). It means at every iteration you shut down each neurons of layer 1 and 2 with 24% probability. The function model() will now call:

forward_propagation_with_dropoutinstead offorward_propagation.backward_propagation_with_dropoutinstead ofbackward_propagation.

parameters = model(train_X, train_Y, keep_prob=0.86, learning_rate=0.3)

print("On the train set:")

predictions_train = predict(train_X, train_Y, parameters)

print("On the test set:")

predictions_test = predict(test_X, test_Y, parameters)

Cost after iteration 0: 0.6543912405149825

<ipython-input-6-e9e79aba8c99>:276: RuntimeWarning: divide by zero encountered in log

logprobs = np.multiply(-np.log(a3),Y) + np.multiply(-np.log(1 - a3), 1 - Y)

<ipython-input-6-e9e79aba8c99>:276: RuntimeWarning: invalid value encountered in multiply

logprobs = np.multiply(-np.log(a3),Y) + np.multiply(-np.log(1 - a3), 1 - Y)

Cost after iteration 10000: 0.061016986574905605

Cost after iteration 20000: 0.060582435798513114

On the train set:

Accuracy: 0.9289099526066351

On the test set:

Accuracy: 0.95

Dropout works great! The test accuracy has increased again (to 95%)! Your model is not overfitting the training set and does a great job on the test set. The French football team will be forever grateful to you!

Run the code below to plot the decision boundary.

plt.title("Model with dropout")

axes = plt.gca()

axes.set_xlim([-0.75, 0.40])

axes.set_ylim([-0.75, 0.65])

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict_dec(parameters, x.T), train_X, train_Y)

Note:

- A common mistake when using dropout is to use it both in training and testing. You should use dropout (randomly eliminate nodes) only in training.

- Deep learning frameworks like tensorflow, PaddlePaddle, keras or caffe come with a dropout layer implementation. Don’t stress - you will soon learn some of these frameworks.

- Dropout is a regularization technique.

- You only use dropout during training. Don't use dropout (randomly eliminate nodes) during test time.

- Apply dropout both during forward and backward propagation.

- During training time, divide each dropout layer by keep_prob to keep the same expected value for the activations. For example, if keep_prob is 0.5, then we will on average shut down half the nodes, so the output will be scaled by 0.5 since only the remaining half are contributing to the solution. Dividing by 0.5 is equivalent to multiplying by 2. Hence, the output now has the same expected value. You can check that this works even when keep_prob is other values than 0.5.

4 - Conclusions

Here are the results of our three models:

| Model | Train Acc | Test Acc |

|---|---|---|

| 3-layer NN with no regularization | 95% | 91.5% |

| 3-layer NN with L2 regularization | 94% | 93% |

| 3-layer NN with dropout | 93% | 95% |

Note that regularization hurts training set performance! This is because it limits the ability of the network to overfit to the training set. But since it ultimately gives better test accuracy, it is helping your system.

Congratulations for revolutionizing French football. :)

**What to remember**:- Regularization will help you reduce overfitting.

- Regularization will drive your weights to lower values.

- L2 regularization and Dropout are two very effective regularization techniques.

Leave a comment